Chinese scientists have drawn the world's first whole genome sequence map of oysters, opening new possibilities for raising oyster production and the development of new industrial materials.

"The genome sequence map was also the first of its kind for shellfish." said Zhang Guofan, chief scientist of the Oyster Genome Sequence Map Project and researcher with the Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Science (IOCAS).

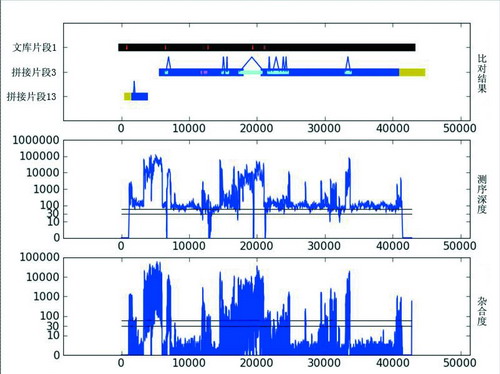

After more than two years, the project team jointly set up by Zhang and Guo Ximing, of the State University of New Jersey, found the oyster genome comprised 800 million DNA base pairs, including around 20,000 genes.

"This finding has proved the extremely high genetic diversity in low forms of marine life and is of great value to oyster breeding," Zhang told Xinhua on Tuesday.

More than 100 varieties of the mollusk are known to exist in coastal areas around all the continents except the Polar regions. The oyster breeding industry is estimated to be worth 3.5 billion U.S. dollars a year. About a quarter of China's marine aquaculture output is generated by oysters.

Li Naisheng, vice-director of Shandong Province Department of Science and Technology, said oyster breeding had long struggled with a low yield-to-area ratio. "Although oysters have high fertility, their offspring are very vulnerable and can die soon after birth."

Li said the genome sequencing map would help scientists breed faster-growing oysters with a higher survival rate.

Zhang Guofan said further study of the oyster genome sequencing map might allow scientists to change its more troublesome habits.

"The oyster is a typical marine fouling organism. They love to stick to the surfaces of ships, increasing resistance, and they block pipes in water and thus hinder marine operations," said Zhang.

"However, by searching for the key gene crucial to such a trait, scientists might be able to entice them to grow independently," said Zhang.

Scientists were also looking at isolating the gene responsible for the oyster's super viscocity for industrial applications.

Zhang said the development of such a material was only at the theoretical stage, but it could be applied in construction, craft production and machinery maintenance.

Ni Peixiang, director of the Shenzhen Huada Genomics Institute, a partner in the oyster genome sequencing project, said the sequencing was "a basic but significant step" and further study would be made on individual genes.

Zhang Guofan said he was dedicated to solving some of the riddles surround the mollusk.

"Why do most oyster offspring die shortly after birth? How come no two oysters look exactly the same? Why is it believed that eating oysters is good for the kidneys? Answers will come from this map," he said.

The world's first human genome sequence map was finished in June 2000. From 2000 to 2009, scientists across the world have drawn whole genome sequence maps for 1,100 species, averaging 118 a year.

Chinese scientists have completed genome sequencing for rice, domesticated silkworms and chickens as well as endangered animals like the giant panda and Tibetan antelope.