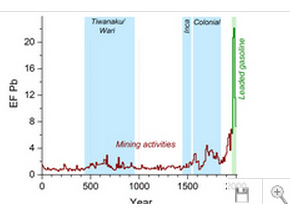

The use of leaded gasoline was the dominant source of anthropogenic, i.e. manmade, lead emissions in South America from the 1960s onwards. The fuel even surpassed the thriving mining industry in this region of the world, which also releases large quantities of lead. In the past, measurements in the Northern Hemisphere had already revealed that emissions from leaded gasoline exceeded those of mining activities. However, such conclusive evidence was lacking for the Altiplano region in South America. On this plateau, located between the western and eastern Andes, extractive metallurgy from mineral ores has been releasing large amounts of lead into the environment since the pre-colonial era.

Record of anthropogenic lead emissions over the past 2,000 years in the Bolivian Altiplano. Shown are lead enrichment factors (EFs) compared to the regional background, reconstructed based on an ice core from the Illimani glacier. Before the use of leaded gasoline (period AD 0–1960), lead emissions from mining activities were dominant, especially during periods of the pre-Colombian cultures Tiwanaku/Wari and the Incas, the colonial era and with the increasing industrialisation in the 20th century (brown, blue). Emissions from leaded gasoline were primarily responsible for the significant increase after 1960 (green). Picture: Paul Scherrer Institute.

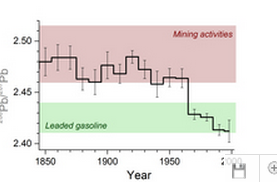

Isotopes are variants of a chemical element that differ from each other in their respective atomic weight. Chemically the various isotopes behave in the same way. Due to their differing weights, however, they can be separated in the mass spectrometer. Lead naturally occurs in the form of eight different isotopes. The four lighter ones are stable, while their four heavier counterparts decay radioactively. The origin of the lead in an environmental sample can be determined based on the different proportions of these isotopes. The researchers have now found the fingerprint for leaded gasoline revealed in the ratio of the two heaviest of the stable lead isotopes. “We detected a lower ratio of lead-208 to lead-207 after 1960,” explains PSI researcher Anja Eichler, the first author of the study. “This isotope ratio deviates from that which is typical of lead from the Altiplano mines, but is in good agreement with the isotope ratio measured in the air in Chilean, Argentinean, and Brazilian cities in the 1990s. The majority of the lead in these air samples can clearly be traced back to leaded gasoline,” adds Eichler.

The study once again highlights the importance of the ban on leaded gasoline for the environment and human health. If inhaled, lead can enter the bloodstream and ultimately the brain, where it poisons nerve cells. Leaded gasoline has already proven to be a key source of lead emissions in previous studies. “We now show that this is also the case in a region in which mining with its heavy lead emissions has been practiced intensively for millennia,” says Margit Schwikowski, co-author and head of the study and the Analytical Chemistry Group in the Laboratory for Radiochemistry and Environmental Chemistry at PSI.