(Text by ZHOU Hui, zhouhui@qdio.ac.cn)

The ocean, according to physical oceanographer ZHOU Hui of the Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOCAS), is a "chaotic yet fascinating dance floor." On this stage, motions from tiny ripples to thousand-kilometer currents twist and interact in a nonstop performance. To understand how this vast blue world shapes our climate, she must solve a fundamental puzzle: how energy cascades from massive, wind-driven currents down to the tiny eddies where it finally dissipates. "The most direct way to address this," ZHOU asserts, "is to venture into the field and conduct oceanographic expeditions."

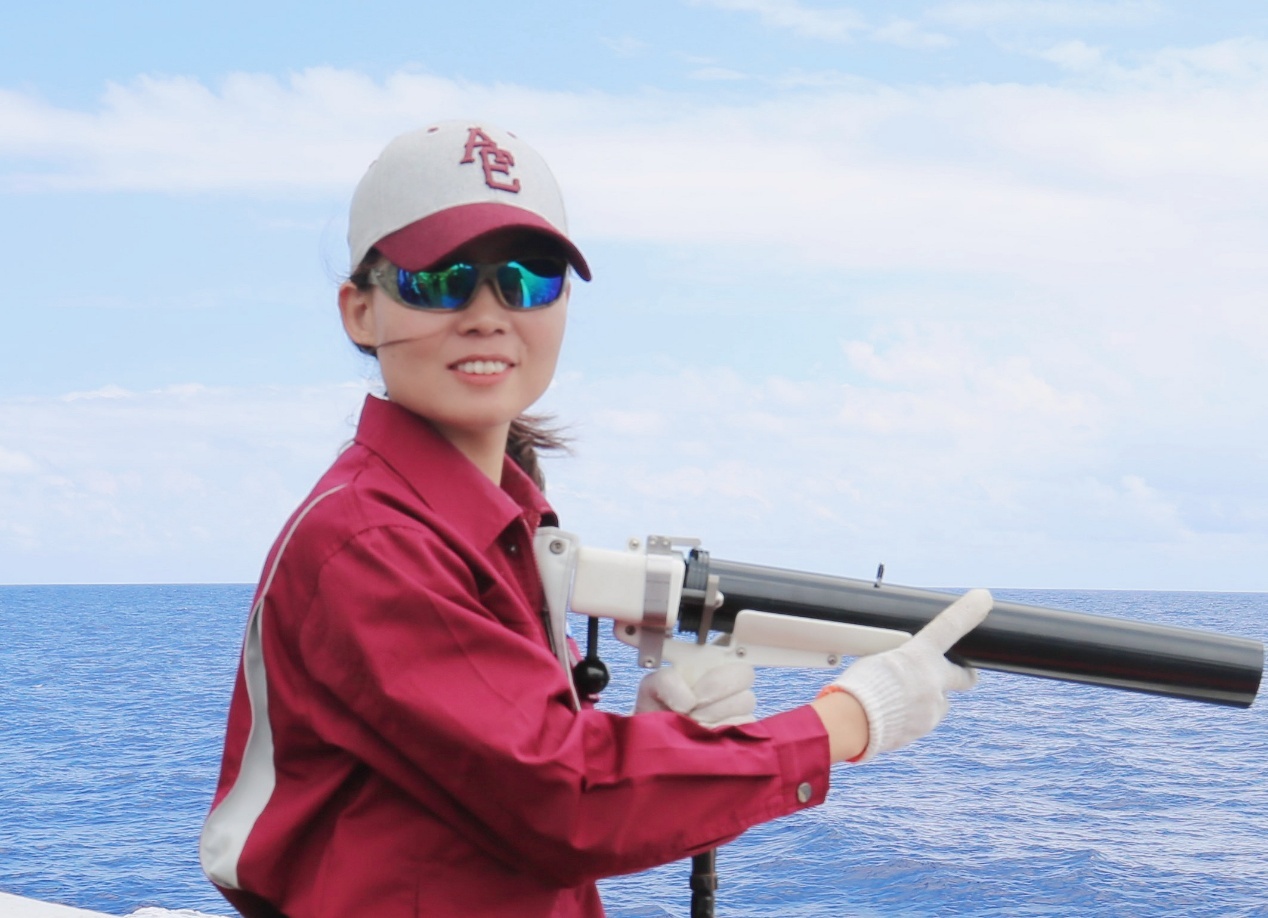

As the first female chief scientist for deep-sea expeditions at CAS, ZHOU has not only ventured into this dance floor but has also led the choreography. For nearly two decades, she has dedicated her life to unlocking the codes linking the ocean and climate, navigating towering waves and hidden undercurrents in the vast western Pacific.

The early morning of 2012 marked the start of ZHOU's deep-sea research career. When the research vessel pulled away from the harbor, what greeted her was not just the magnificent seascape, but also seasickness severe enough to overwhelm most people. During the first week of every voyage, she could barely eat or drink, often vomiting until she was completely exhausted. "Lying in the cabin, even breathing felt strenuous," she recalled. Yet, she views this crucible not with dread, but with deep gratitude for the resilience it forged within her.

In 2014, at the age of 36, ZHOU took on the role of chief scientist for a research cruise, becoming the first female "helmsman" in CAS's deep-sea exploration team. "It's not that I'm particularly outstanding; I just refuse to give up," she says with characteristic humility, downplaying the countless days and nights spent battling the elements that led to this historic achievement.

Among ZHOU's expedition experiences, the 2016 National Day open-sea mission stands out vividly. Back then, she led her team to the 5,000-meter-deep sea, aiming to retrieve three Pressure-Inverted Echo Sounders (PIES) that held critical data on the 2015–2016 El Niño event. "This data will provide invaluable support for us to more accurately predict climate anomalies. No matter how hard it is, we must bring it back," she told her team, making a solemn commitment before departure.

The challenge was unprecedented. No Chinese research institution had ever recovered PIES from such depths. ZHOU and her team were venturing into uncharted waters. After a sleepless night spent meticulously planning every detail, they issued the release command in the pre-dawn darkness. What followed was an agonizing 90-minute wait, the deck so quiet they could only hear the waves lapping against the hull. "Everyone clenched their fists and stared into the pitch-black sea," ZHOU remembered. The wait stretched on until dawn, with still no sign of the equipment. Her spirits plummeted.

After battling seasickness and sleepless nights, the thought of losing the precious data was devastating. But defeat was not an option. "I knew searching for lost equipment at sea was like looking for a needle in a haystack," she said firmly, "but my stubbornness made me try." She convened an emergency meeting and proposed a daring plan: deploy a glider to map surface currents and wrap a radio receiver in tin foil to boost its signal. For the next three hours, her team worked tirelessly, her bloodshot eyes fixed on the monitor. Then, a faint signal appeared 13 kilometers away. A shout of excitement erupted—there it was, a small white sphere bobbing on the waves. By then, ZHOU had been awake for 40 hours.

New challenges soon followed. In 2017, ZHOU led her team in using a microstructure profiler for scientific research for the first time. This equipment was worth over one million RMB, and due to the high risk of loss, almost no insurance company was willing to underwrite the venture. "If we lose this instrument, the entire responsibility will fall on me," she said. That week, she slept only three or four hours each day, while simultaneously fighting off seasickness and directing the deployment of equipment and data collection.

But fortune favored the bold. The observations were a spectacular success, revealing a new pathway for mixing in the equatorial interior ocean. This achievement was highly praised by internationally renowned oceanographers. For ZHOU, it was a moment of quiet, overwhelming emotion. "All the hardships," she thought to herself, "have been worth it."

Over the past nearly two decades, she has witnessed the rise of China's marine science. "In the past, we lacked the opportunity to test our own scientific hypotheses in the deep sea," she reflects. "Now, our research vessels traverse the globe, empowering us to validate our theories on the world stage." As a woman in science, she admits to sacrificing more—time with family, pushing past physical limits. But her passion for the ocean and her country propels her forward.

Today, guided by the national maritime power strategy, her deep-sea exploration continues. "Dare to dream, persist through hardship, and you too will help China reclaim its glory as a great maritime power," she says. Through her extraordinary journey, ZHOU Hui embodies and illuminates the profound blue-sea aspirations cherished by all Chinese people for the younger generation.

ZHOU Hui was deploying XBTs (Expendable Bathythermographs) during the 2015 Western Pacific Ocean Research Cruise. (Image by IOCAS)

ZHOU Hui was speaking on China's deep-sea exploration development as an invited guest on CCTV in 2017. (Image by IOCAS)

(Editor: ZHANG Yiyi)